When we talk about “the yeshiva world” we most often refer to the yeshivot established in Greater Lithuania in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and their transplants in the US, Israel, and elsewhere beginning in the interwar period. Rarely is there discussion of other yeshivot, and when there is, they are generally given short shrift.

There is no doubt that, structurally, the Lithuanian yeshivot differed from other yeshivot. One salient difference is that many of them functioned independently of the host communities and had their own fundraising networks. I recall learning this from Prof. Shaul Stampfer in the summer of 1999 and finding it to be quite a revelation. But there were, it must be noted, community-based Lithuanian yeshivot as well, most notably the Ramailes Yeshiva in Vilna. But Lithuanian yeshivot are not our topic today.

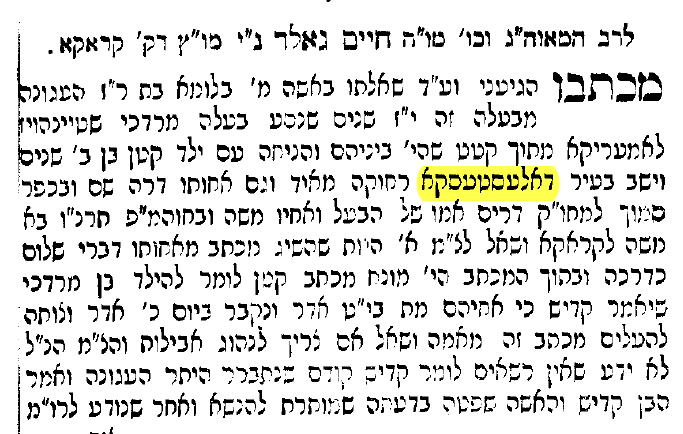

A number of months ago, I noticed that some books include rosters of yeshiva students within presubscriber lists (prenumeranten). Here’s an example that comes from a book called Shulhan shel Arba, a treatise on proper conduct at the table, composed by Rabbeinu Bahya ben Asher, a disciple of Rashba (late-13th and early-14th century Spain). In 1939, Rabbi Yitzchak Essner, a resident of Presov, (Czecho)slovakia, reprinted the work at Vranov (nad Topľou) with his own commentaries. There are four pages of prenumeranten, including sub-lists from five different Hungarian yeshivot. Here’s the beginning of the list from the yeshiva in Dunaszerdahely:

Few outside of those who really study Hungarian Jewish history have even heard of Dunaszerdahely, know that it was the home of R. Yehuda Aszod, or are aware that it was actually home to yeshivot. But it was. A glance at this list (there are 2 or 3 more students on the next page) shows that, contrary to the common understanding, the students were not just local boys, but actually came from fairly far away. Their hometowns are listed, and I have highlighted them in green. Here’s a map of the hometowns:

And this is but a small cross-section of books bought by yeshiva students in Dunaszerdahely. Of the 20 or so books with Hungarian yeshiva subscribers that I have mapped thus far, about 5 have lists from Dunaszerdahely, and there were between 12 and 41 subscribers to each book. (Lest one consider that fluctuation in the size of the yeshiva accounts for the difference, note that the books in question were all printed between 1938 and 1940.) Here’s a look at the hometowns of all subscribers from the yeshiva of Dunaszerdahely. It’s zoomed out a bit to include the one subscriber from Poland and one from Prague:

There are about 120 books that have lists of Hungarian yeshiva students (about 2/3 of these were published between 1920 and 1943), and thus far I have encountered about 35 yeshivot, which is a fraction of the 230 yeshivot listed by Rabbi Dr. Armin Friedman in his dissertation on the subject. Some of the yeshivot were tiny, but there were over 300 students at the yeshiva in Munkacs in the early 1940s.

Interestingly, I have not found such lists for yeshivot in Lithuania – or anywhere else, for that matter. This seems to be a strictly Hungarian phenomenon. It could be that it is a matter of social class. Interwar Hungary (including regions like Slovakia, Transcarpathia, and Transylvania that had been part of Hungary until 1920) was very much middle class. That does not mean that all the students had money, but that enough of them had disposable income to make it worthwhile for an author or agent to sell in the yeshiva.

The yeshivot were also somewhat institutionalized. Each one had a system of gabba’im in charge of various aspects of yeshiva life. The red highlighted text above identifies a student as ג”ר דחמ”ז – gabbai rishon de-hevra mezonot. He was in charge of either organizing meals for students at the homes of local community members or of procuring the food to be served in the yeshiva kitchen. While some yeshivot were linked directly to the rosh yeshiva (often the local rabbi), and followed him if he moved, by the late 1930s, several yeshivot had permanent buildings and several staff members, and so had attained a degree of institutionalization and perceived (though, in hindsight, tragically illusory) permanence.

This post covers much of the ground from my presentation at the AJS conference in Chicago last week. There’s a lot more to investigate and discuss. I’m posting the map from which I took the images above. As you will see, you can filter it by several variables. For example, you can look (better in a separate tab) at a particular book, a particular yeshiva, or a particular town. It includes some 2,000 data points, which is really only the tip of a very large iceberg.