We have been following the “Jewish Miscellanies” blog by Jeffrey Maynard for a while. He consistently posts about the rare and interesting books in his collection, mainly, but not only, of Anglo Judaica. Some of the books in his collection have really interesting Prenumeranten lists.

One such book that he wrote about is “Zecher Ov” by Rev. Hanokh Henikh (Henry) Olivenstein, published in 1916. The author was a “Swiss-army Jew” who served communities in Wales. The subscribers include people from lots of places in the UK and elsewhere, but there’s a remarkable cluster of tiny little hamlets in southern Wales, where he ministered. Most of these places do not appear in Kagan’s index. Here’s a screenshot; you can explore further by typing “Wales” in the “English Name” text box in our Searchable Map.

Since the last update of the map, we’ve identified another place in this list: לאמבאראדאך is Llanbradach, Wales. The only place on the Zecher Ov list that we have not identified is נאוי which is in France (or was in 1916).

More recently, Maynard wrote about a volume of R. Meir Dan Plotzki’s Hemdat Yisrael that was published in 1924. The subscribers are from Belgium, England, the US (plus R. Yehuda Leib Graubart in Toronto), and Argentina. It’s a fascinating list that includes many American Orthodox rabbinic and lay leaders. We will have more to say on that in the future, as there are some similar lists.

One interesting feature of this list is the way that some city names are spelled. We have already written how Yiddish place name spellings are phonetic, and so subject to lots of variance, based on dialect. There is also variance based on regional modifiers. For example, if you live in Frankfurt am-Main, you refer to your hometown as Frankfurt. Likewise if you like in Frankfurt an der Oder. In some circumstances, however, you will have to specify which Frankfurt you refer to.

Predictably, there are dozens, perhaps hundreds, of places whose names mean, simply, “New City”. This includes anyplace named Neustadt or Nove Mesto or Villanova or Ujhely. Naples and Nablus and Newton fit the pattern, too. So when a Hebrew source mentions ניישטאט or עיר חדש, it can be a challenge to disambiguate.

Fortunately, most such places have an additional modifier. To take an example of a pretty famous place, consider Brisk. Today it is known as Brest, Belarus, and it’s easy to see how Brest and Brisk are cognates. But at various times, it was known officially as Brest-Litovsk. What’s the Litovsk? It simply means “Lithuanian”. So the Russian Brest-Litovsk, the Polish Brześć Litewski, and the Yiddish בריסק דליטא simply specify that the reference is to the Lithuanian Brisk, not a different one. In this case, the other one is Brześć Kujawski, בריסק דקויא, or Brest Kujavsk, in Poland.

[Sidebar: The idea that some people call Satmar “Sakmar” because it otherwise means “St. Mary” is silly. As the Brest/Brisk example illustrates, the t/k shift happens elsewhere, and in no language does Satmar or Satu Mare mean “St. Mary”. Perhaps one will argue that just as religious Jews changed Satmar to Sakmar to avoid invoking St. Mary, they changed Brest to Brisk to avoid naughty thoughts? There are other examples – like Saponta, a town very close to Satmar, which is known in Jewish sources as Spinka. At some point, we will post about all the different places in rabbinic sources that are named for saints and other elements of Christianity.]

We do not realize it, but we often do the same thing. To disambiguate the many Springfields, Salems, and Portlands in the USA, we use the state name. Locally, Springfield is Springfield, but in many cases one will need to specify whether one is referring to Illinois, Massachusetts, the fictional setting for “The Simpsons”, or one of the many other Springfields.

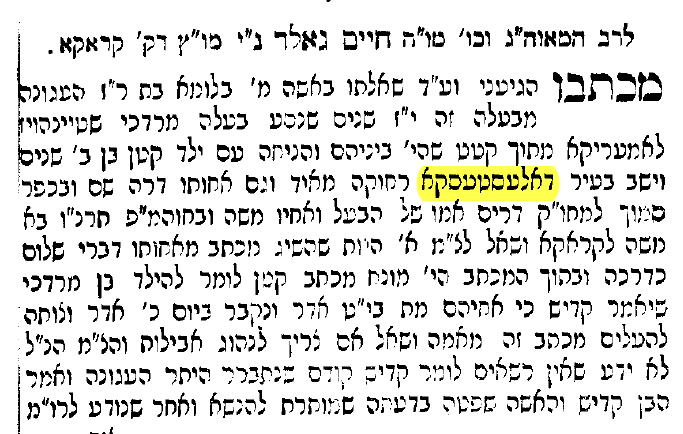

When the person writing out the subscriber lists knows about this, they will account for it and use a format similar to the familiar [City, ST] format. But what if they are not? Funny things happen. Consider this responsum from Maharsham:

The דאלעסטעסקא mentioned here is none other than Dallas, Texas. It got all smushed into one word, which is typical for European place names but not American ones.

That’s just one example, though. In the subscriber list for Hemdat Yisrael, we find no less than six examples:

האליאגמאס

ספרינגהעלדמאס

פאלריווערמאס

מאלדענמאס

דענווערקולרדא

לואי סווילקי

If you want to try to figure these out on your own, stop reading here. We will ID the places at the end of the post.

One peculiar thing here is that 4 of the 6 examples are from Massachusetts. Massachusetts is better represented on the subscriber list, as there were lots of small Jewish communities there, but that does not explain why 2/3 of these examples are from one state. Disambiguation can perhaps explain one of these examples, though we are doubtful about even that.

I (Elli) think that this reflects a peculiar habit of Massachusettsans to add “Mass” as a sort of suffix to cities in that state. If you heard a Massachusettsan speak and had no geographical knowledge, you might easily conclude that there’s a place called “Woostamass”. The transcriber of the subscription lists can easily have made such mistakes.

Anyhow, the places where city and state are contracted into one word (or two oddly-parsed words) are:

Holyoke, MA

Springfield, MA

Fall River, MA

Malden, MA

Denver, CO

Louisville, KY

If you have another theory, we’d love to hear it!

Neuilly-sur-Seine?

We now think it’s Neuvy…

The problem is that there are several places with that name!